-

AutorPublicaciones

-

June 22, 2024 4:27pm #31822Yeah, thanks for the reply. I know the drawing for the trash can idea. I got the special perk, that my hoarder syndrome kicks in in regards to my drawings, so I can report that I can add all the stacks of Din A4 paper in my room to about a total of 1 meter in height, plus another stack of about 30 cms of Din A3. Functionally it is the same though, as I am pretty certain, that all those papers will stay untouched until the day either I or someone else decides it's time to move them to the next recycling station.

I mean, for me trying to be honest with myself will always have to include being ready to be critical with my actions. And if I purposefully look critical at my drawing habit, I can see a lot of at least ridiculous aspects. Purposefully devoting hours per day to staring at a screen and scribbling on paper isn't exactly a fulfilling way to satisfy social needs. It might be well a classical symptom of an avoidant personally type. Dreaming about ever "mastering" the craft and being recognized for it is pretty clearly a grandiose narcissist phantasy.

But then, all critic is incomplete without considering the alternatives, and well... I realized about a decade ago, that I am definitely an addictive personality. Joined Narcotics Anonymous, quit the drugs,... except coffeine and nicotine and industrially processed sugar and electronic media,... well, I at least quit alcohol and the illegal stuff. But then I realized, that when I am sober, I just don't enjoy being around other people. It's not a problem of social skills, I work as ambulant nurse, and have to manage a whole lot of drama on my shifts, and from the feedback of my patients and co-workers, I am fairly competent at it. Just, given the choice, I prefer not to.

According to NA dogma, addiction is ultimately caused by the God sized hole in ourselves, that wants to be filled. The same idea from a more philosophical point of view, with a distinctive atheist and existencialist bent, our behavioral instincts are bound to function according to a purpose. Just that there is no objective "purpose" to be found in the material world, and we are both free and damned to make up our own. (shoutout to Sartre, R.I.P.)

So, art, drawing.... why not? The dream of achieving mastery may be grandiose, and the chance to ever succeeding in my lifetime may be small, but it's probably still a better chance than in buying a lottery ticket every month, and defintely cheaper.

Let's go beyond asking the question why gaming is more seductive than practicing drawing skills as a rhetorical device, and try to set maximizing time spent drawing as axiomatic goal, that shall no longer be questioned.

Is the frustration of failing our artistic goal for a drawing the problematic part? Frustration is definitely a constant companion while honing our skills, maybe an inevitability, that can never be overcome. But then, ruining a good drawing with a few mismeasured lines is defintely a lot less embarrassing than piloting the highest tier heavy tank in a World of Tanks match, and getting booed by the whole team for being sniped in the first minute without even connecting a single shot myself, and that amount of shame did not stop me to continue tanking.

I know, that I am also capable of working a total of 24 hours of shift in 48 hours time, and between proccessing Hamburg's heavy car traffic, and switching on the fly to soothe all the minor and major ailments my patients struggle with, that certainly also generates a whole lot of frustration.

I think the difference between that and drawing, is the little sibling of the big allmighty purpose, the small and actual task at hand. Whether in gaming or in working shifts, there is always a clear task for the next minute, and the next and the next. I might fail at the task, I might even misunderstand the task, but I never have the urgency to come up with a new task on the spot, as I always feel certain what the task is.

In art, there is always a million possible tasks to chose from. Do I simplify the pose, mannequinize, box in the perspective, measure precisely or exaggerate in big lines, is it time to define more landmarks to get the big proportions correct or is it better to just eyeball the proprtions directly and fill in the details later? Sometimes, all too rarely, I get in the flow, and the task at hand becomes so clear, as if the reference just dictated it.

I think at least for me the next step in maximizing my time spent drawing is understanding the process of setting tasks while drawing better.

Well, next actual task for me, my late shift is about to start in an hour and a half, and I definitely have to get in a power nap before that.

While I don't enjoy spending time with people, I do enjoy trying to formulate elaborate thoughts in writing, and I also enjoy reading other people's thoughts on a subject, so, maybe this thread will grow even longer, either from more ideas from myself, or from other people chiming in with their thoughts.June 22, 2024 4:51am #31820Hi joiy.

Good that you found back to the drawing board. I like the simple shapes you settled on. Your focus on proportions works, the relation between head, torso and legs is natural.

One thing, that I am just not sure about: did you draw the figure diagonally on purpose? It could kind of make sense, but there is a bit of a doubt, as the diagonal tilt could also be caused by starting boldly with the tilted shoulderline, and then being tempted to stiffen the pose by "adjusting" the central axis to reduce the impact of your initial decision.

There would be two tips that would derive from that:

a) work with a "plumbline", that is, make sure, that points on the figure that are directly vertically aligned on the reference stay directly vertically aligned on the drawing.

Typical points to look out for on an upright figure are, for the head, the tips of the jaw and the nose, to find the center line for the face, for the upper torso the jugular and solar plexus, which determine the orientation of the ribcage, for the lower torso the belly button and the crotch, which indicate the position of the hip. Imagine a vertical straight line through the figure and observe how much these points are to the left or right of it.

and

b) try to understand to how much of a degree the shoulder joints are independent of the upper torso and their range of motion.

Your base construction for the upper torso at the moment seems more or less a flat rectangle, which is a bit the worst of two approaches.

For basic underlying shapes, I would recommend mentally separating the upper toso into ribcage and shoulders. The best form for the upper end of the ribcage is the top of an egg. The very top of the egg connects to the neck exactly at the jugular, where also the collar bones start, that connect to the shoulder joints. Off course the shoulders obscure most of the eggform of the ribcage, but keeping it in your mind's eye makes the analysis of that body part much easier.

There is an idea to reduce most of the body forms into boxes, to get more into a perspective view, but the thing about boxes is, that they are there to indicate three dimensionality, and even if you had that in mind, the rectangle you chose is still flat, and also, perspective drawing does not change that the shoulders have a degree of individual freedom from the ribcage.

On another note, I think you should spend a bit of warm up time practicing long straight lines and clean curves. Just put two points on the paper, not too close to each other, hold your pen just above the paper and repeatedly move your hand like you were drawing (make sure, neither your wrist nor your elbow is resting on a surface, so you initiate the movement from the shoulder) until you see a shadow of the line appear, then draw the line in one motion exactly straight and exactly from point to point. The focus should be completely on the fine coordination of all your muscles involved in that movement.

For practicing curves, just draw clean circles freehand. Repeat every circle twice without stopping. Draw circles in both directions. When your circles over time become cleaner, and you want to spice it up, draw random uneven crosses, and start matching them with ellipses.

It's not that your line quality is absolutely horrible, but it isn't great either, and the earlier you start practicing line quality, the less you have to retrain later.

Just a few minutes of this stuff before the start of every drawing practice will make a world of difference in how you move your pen in a relatively short time.1 1June 20, 2024 3:45pm #31815I hit my 300 hours spent drawing on this site today. I also checked my old account on quickposes.com, where I have 13 days, 20 hours, which should be 332 hours total if my math doesn't fail me. I went through the drawabox tutorial for the first 5 lessons, including all the challenges, and worked through a Figure drawing course by proko. That should be at least 200 more hours on total. The I spent quite some time "urban sketching", but it is a bit hard to divvy up, how much of that time was spent wandering around, and how much I actually had my pen hit paper, but I'll take 100 hours for that.

So, probably I spent 1000+ hours drawing in the last 5 or so years. There is this urban myth, that it will take 10.000 hours to achieve mastery. At my current pace, that would take until the year 2060, and I'll probably run into natural decay of my mortal shell by then, as I would be close to 90 years old.

If I could increase my time spent drawing to an average of 3 hours a day, I could get there in mere 10 years. If I matched 6 hours a day, it would be less than 5 years. But at the moment I barely manage to do 3 hours a day under ideal conditions, on my days off, when I am in productive mood, and nothing distracts me, on so many other days I barely manage to get to the end of a 30 minutes class.

Then I look at my account on World of Tanks, a game that I quit, because of the toxic community, and I had 15.000 games on it. With an average of maybe 10 minutes per game, that's already 2500 hours of my life wasted there, and I am not even good at that game. And WoT isn't the only game, that is tempting me, and let's not talk about all the hours just staring at you-tube videos with glazed eyes.

What makes it so hard to spend time on improving myself, instead of consuming entertainment?June 14, 2024 2:53am #31769thereisnogestureinfacesthereisnogestureinfacesthereisnogestureinfaces.... human beings just don't gesticulate with their noses or eyebrows! Unless we are talking about elephants or octopods, there is no gesture in facial expression!-

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 14, 2024 12:06am.

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 14, 2024 12:06am.

-

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 14, 2024 12:06am.

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 14, 2024 12:06am.

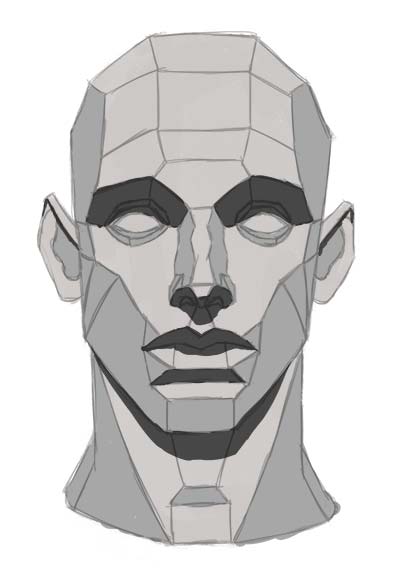

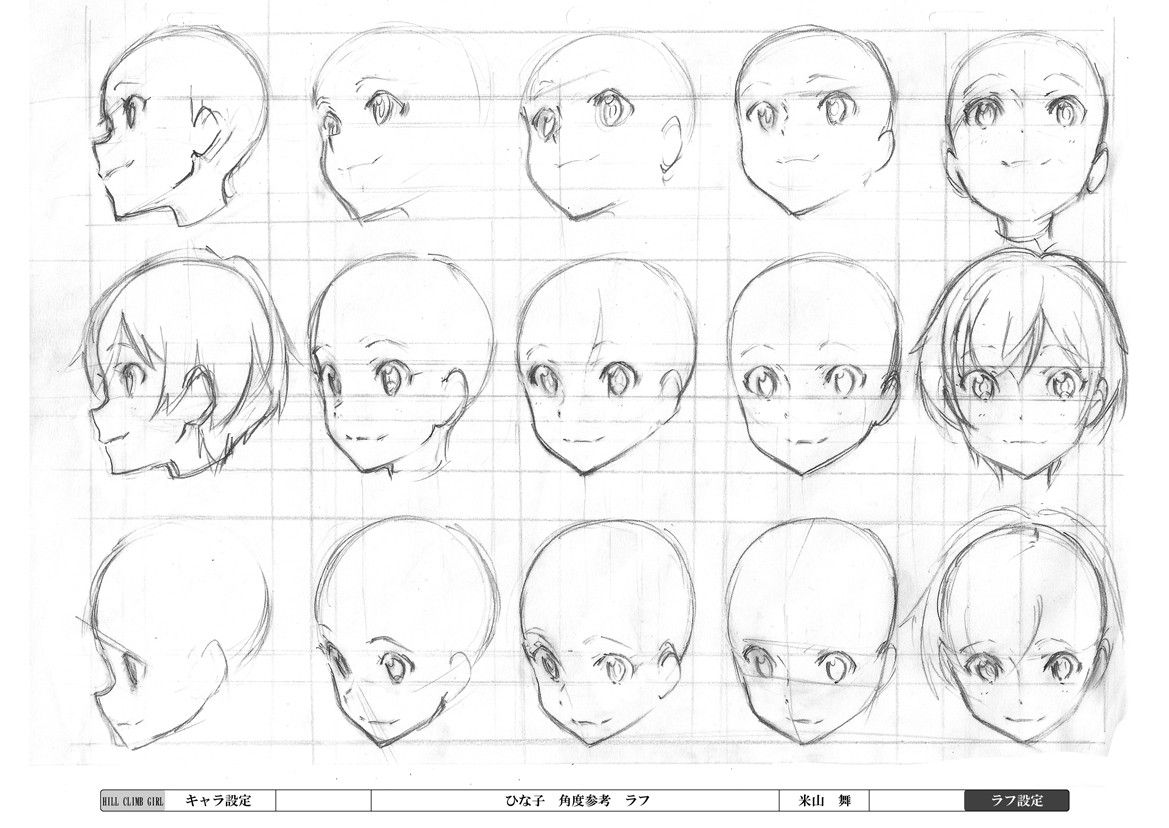

June 13, 2024 1:04pm #31765Heads work quite differently from poses, as the proportions of a head are very uniform. The big shapes of a head with an angry face and the shapes of a head with a crying face or the shapes of a head with a laughing face are still basically the same.

This is, why there are various abstractions of famous artists, that have defined such shapes and proportions.

Andrew Loomis:

Frank Reilly:

Henry Bridgman:

Steve Huston:

John Asaro:

or even japanese industry style, which sacrifices natural proportions for style, and is mostly shared by a lot of japanese artists, look for Manga or Anime style:

The problem is, that in drawing faces and heads, other than with poses, you generally don't start with capturing the emotion, but instead you use the idealized form of a human head, and mostly only change the direction in which it is looking. The emotional expression of the features isn't really part of the big simple shapes you draw in the first minutes, these are basically treated as rendering details, that are added on top of the human head.

Memorizing at least one of the abstractions above is really helpful for drawing heads or faces. You don't have to sketch it out in all details at the start of every drawing, but the process of drawing such an abstraction will teach you which proportions and shapes to measure and uphold, even when drawing "freehand"

Most popular abstraction for general purpose is Loomis, because it is simply the easiest to learn and good enough for 90% of basic drawing needs. You will find more detailed tutorials for each of those abstractions all over the web, by just using the names as search words.-

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 13, 2024 10:10am.

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 13, 2024 10:10am.

-

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 13, 2024 10:17am.

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 13, 2024 10:17am.

-

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 13, 2024 10:21am.

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 13, 2024 10:21am.

June 13, 2024 11:50am #31764Polyvios, sorry, this wasn't an answer to your post. But the post I originally answered to has obviously been deleted by its author. But there still isn't gesture happening in the face, in the face it's called mimic or facial expression, and it's called differently, because it actually also works differently than gesture.

The features of the face just aren't limbs, they aren't connected by joints, and they don't use massive changes in silhouette to communicate an action or a feeling. Tiny differences in muscle movement can make a giant difference in emotional content of an expression. Fear and laughter, anger and bewilderment, sadness and boredom, those expressions are so close to each other that a lot of people seriously struggle to tell them apart when actually talking face-to-face with another person.

Yes, an artist, who is able to differentiate between such subtle nuances with as few lines as possible is certainly recommendable, but just forcing yourself to capture such nuances in 30 seconds from random photographic references won't teach you how to find the exact decisive lines, that are needed.

I understand what you are saying and mean about the goal. I just think that in this case short timed drawings are the absolutely wrong tool to achieve that goal, and are actually a trap. You see what I am saying and mean? I don't disagree about your intention, but about the proposed way to get there.

Gesture is about big and bold movement, it's like a hammer, while mimic or facial expression is about little precise movements of tiny muscles, more like a screwdriver.

There are similarities between a nail and a screw, but the old saying that if you only know about hammers you treat everything as a nail is still true.

And this certainly not about you personally Polyvios, I am so invested because that very misconception, trying to learn facial expressions the same way as gesture is best learned, is so often thrown around by people, who just aren't very good at drawing faces.-

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 13, 2024 8:57am.

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 13, 2024 8:57am.

June 12, 2024 11:42am #31757What is the gesture of a face? Between gesture and mime, mime is generally associated with faces. And mime isn't defined by big motions, but by subtle details.

If someone is "gesticulating wildly" with their cheeks, nostrils, and eyebrows, it's time to call the ambulance, as they might be suffering from a seizure.

Also, the big shapes and proportions of all faces are generally the same. You can practice them, but you don't need specific reference for them, as there is no big change in silhouette. For studying the shapes and proportions of faces, it's useful to just drill abstractions, Loomis, Reilly, Bridgman, Huston, or even japanese industry manga faces if you prefer that style and favor expression over realism... but hurrying them doesn't improve the practice, as they are by their nature as abstractions already idealized.

Look, I am not asking you to show how you would do it, as that would be arbitrary and unfair, depending on your amount of practice you had. But find anyone, who is good at portray drawing OR caricature, who teaches starting face drawing from quick sketching at a pace of a minute or less. Sources from the internet, sources from literature, anything.

Most people have conscious control over their jaws, lips, cheeks, nostrils and eyebrows to form an expression, but the motion of the facial muscles is extremely minute compared to the muscles of limb and torso. And there is general consent in the art community, that it is good practice to draw from big to small. Timed practice from reference with faces would mean, you deliberately practice starting with tiniest details. It's a trap, don't do it.

If you want to use this site to practice drawing faces, don't use the "class" feature, use the "all the same length" feature, and chose at least 5 minutes or 10 minutes, or use the self defined length and enter 3600 seconds.

There is still the same risk of getting lost in spending oozes of time rendering a flawed construction, but other than in poses, you can't just avoid it by putting yourself under time constraints. You have to know about it, and use self discipline to stop yourself, when you go into rendering mode, while your constructtion is still flawed.-

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 12, 2024 9:06am.

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 12, 2024 9:06am.

-

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 12, 2024 9:27am.

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 12, 2024 9:27am.

-

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 12, 2024 9:58am.

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 12, 2024 9:58am.

-

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 12, 2024 10:07am.

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 12, 2024 10:07am.

-

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 12, 2024 10:20am.

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 12, 2024 10:20am.

-

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 12, 2024 10:22am.

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on June 12, 2024 10:22am.

June 10, 2024 12:09am #31747I definitely love your focus on clear and crisp shapes. I think you have an incredible effective way to inform about shape and posture on a glance, and I think the silhouette is strong enough, that you could even scale them down to very tiny depictions without losing any of that message (That is not meant as an actual suggestion for you to do, just as a mark of quality, that you could do it.)

At the moment you are basically using blue as a substitute for black, staying in a digital mode. And I must totally admit, that I can't tell you much about truely dipping into multi-color, as I have been postponing that step time after time.

I occassionally took a look into tutorials, and it's just a whole new can of worms compared to "simply" drawing,, with local colors modified by the color of reflected lights, decisions about saturation and using greyscales to harmonize color composition, new forms of contrasts, emotional "meaning" of individual colors or specific combinations of colors, deciding about a unified palette of colors for diverse effects.... maybe I shouldn't have looked so closely into all of the possible aspects, because now I am scared.

One name I remember from a guy who does great work with gouache and explains his thoughts while doing so was James Guerney on youtube.3June 4, 2024 12:14am #31710I think you are running into a typical problem: You try to solve the whole figure from amassing lots of details, but you don't have an underlying system to organize proportions and relations.

It will work kinda for a while. If you can focus well, you can compare all the relevant relations between two details, between three details, four details,... but with everything you add, you also add a new artistic decision, which you have come up on the spot, and therefor have to keep in the back of your mind. And at some point, you are just bound to lose track, and suddenly the one detail, which should be in a direct vertical line under that other detail just isn't, and the one detail, which should be approx. twice as big as that other detail just isn't, and there are some lines in your drawings, which you just no longer remember why you drew them, and the lower bound of your shoulder joint connects to the upper bound of the biceps instead of the lower one....

You said you bought a book about anatomy for artists, and just stared at the details. Yeah, I remember being pretty much in the same situation. The problem is "anatomy" isn't "anatomy", and being inspired to juggle even more details doesn't help you with your proportion problems. What you need is a hierarchy of anatomical landmarks, so you can sketch out the big proportions quickly and correctly, and only then start to fill in all the pretty details.

We had someone here on this page a long while ago, who actually used such an anatomy for artists book in the right way, and it was jawdropping to see. They had a very crisp and abstract mannequin of the human form, a box for the booty, line of action connecting it with the box for the ribcage, and the circle for the head, joints indicated, tubes for the limbs, whole human form done in purely primitives, but always with just enough lines to indicate the third dimension. The pose of the abstract mannequin exactly matching a reference photo. Then they used their anatomy for artists book to exactly identify a specific group of muscles and drew them onto their mannequin, trying to observe exactly, how those muscles stretched, bent, contracted or expanded on the reference.

So, that pretty book you have isn't exactly useless, it is just like you grabbed a math book about calculus, while you are still struggling with the concept of basic multiplications.

Learning to start with determining the scale of big forms before you focus on detail work is pretty much a universal concept in all of drawing, landscape, still life, portraits, poses, graphic novels, giant murals or tiny newspaper adds. In drawing poses this means getting used to the proportions and scale of motion of the human torso and head and limbs, until you really stick to them automatically, and no longer have to spend your mind on measuring them out painstakingly and constantly remembering all the relations you designed for your current drawing.

And the efficient way to get to that point isn't by starting with loooong paintings, that will just exhaust your focus and never get finished. You say 30 minutes is too short? Try to use that time to draw 60 30 second "poses", not hurrying, but just practicing finding the first 3 or 4 lines in a calm drawing speed over and over, and you probably learnt way more from that. (Actually, doing half an hour of 30 second shorties is a bit too painful. Just use the class option in the menu, the slightly longer sketches that follow will give you feedback about the purpose of your shorties, as the goal of every shorty is to be the perfect start for an epic longform work)

And yes, Proko has been mentioned already, so let me add to the cultish fanboy atmosphere, to point out one of his older courses, the one that I followed several years ago: https://www.proko.com/course/figure-drawing-fundamentals/overview

I can say, it did work for me. The pricetag for the premium course seems steep, but Proko has a bit of a strange pricing model. All the essential informations are in the basic course, the premium course seems more like a huuuge buy-me-a-coffee option, that rewards you with a bit of nice bonus material. I did buy the premium stuff, after I finished the basic course, not because I felt it was lacking and needed something extra, but because I had the money and considered the value of what I had already learned to be in a fair relation with that amount of money. So, my recommendation, do the basic course, decide for yourself if you ever want to pay for the premium.2May 31, 2024 11:13pm #31696A short tip, and it is so short and simple, that it sounds stupid, but when I had my urban sketching phase I found it incredibly relevant to repeatedly remind me while drawing:

MAKE SURE VERTICAL LINES ARE ACTUALLY VERTICAL WHEN DRAWING THEM!

I mean, OK, if you decide to draw the scene at an angle, then they are obviously diagonal, and if you go for extreme prespectives, there can be considerations, too. But I caught myself constantly losing the vertical out of a simple mistake. Usually on the left side of the page, they were still vertical, while towards the right side they started to tumble over, just because it was biomechanically more convenient to pull the pencil directly towards me. (I am right handed)1 1-

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on May 31, 2024 8:15pm.

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on May 31, 2024 8:15pm.

May 30, 2024 12:30pm #31686A bit of a strange question, but no, you aren't obligated to anything at all, unless someone pays you big monies for drawing one way and not another way. And to convince anyone to ever pay you monies, you first of all need to be able to draw stuff, that looks cool. If someone needs a perfectly realistic depiction, they will probably ask a photographer, not a draftsperson. Heck, as you are still working from a photographic reference, they can just use the reference instead!

If anything, you are obligated to make stylistic choices. That is what sets you apart from a xerox machine or a cheap filter software. The end goal is to be able to make them consciously and deliberately, and to keep your stylistic decisions consistent enough to let the viewer intuitively understand and appreciate them.

Talking about looking cool and your ink and watercolor drawings: Yes!!! A thousand times yes! This looks way cooler than your too smooth graphite gradients. These shapes are quick to pick up, and they convey all the informations about the body in space, that you were formerly losing with your blended transitions.

There is one thing you could try: Buy yourself grey ink. Then draw the darkest values in black ink (like you did) and the middle tones in grey ink, and you are automatically forcing yourself to break down the figure into 3 values. If you watch any tutorial about rendering, this separation of the object into three distinct values will ALWAYS come up at some point.

If you want to check out a really classical (and classic looking) impression, you can aim for the rule of thirds, and try to approximately match your darks, middletones and brights in size of area over the whole painting. It's ofc just a rule, not a law, but if you get it done with nice shapes your results will be on a whole new level.

(Footnote: You should never break a law. You should never break a rule, unless there is a specific, obvious, and undeniable reason to break it. There are generally no laws in art, but the rules you obey define you as an artist.)

If you aren't planning to hit the art supply store anytime soon, you can substitute the grey ink for any watercolor of your choice (blue is perfectly fine) Just try to keep the application of the watercolor as uniform and flat as possible, so you achieve a clean separation of darks, middletones and brights. Focus on shapes and lines alone, and don't get tempted back into gradients for now.

Practice this first, and you will already achieve a smooth, but not boring, looking and deliberate finish. Once, if ever, this separation really becomes so second nature to you, that you get bored of it, then you can progress by for example replacing the mono-valued planes with hatching or crosshatching, or to start breaking down the figure into even finer shades of gray, so you can approximate your graphite gradients without losing information, or you can start to investigate color theory to dip into full painting.

Tried to put the theory to practice. This is how it looks when I do it (Not so happy about the linework today)

1 2-

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on May 30, 2024 9:57am.

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on May 30, 2024 9:57am.

-

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on May 30, 2024 1:26pm.

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on May 30, 2024 1:26pm.

May 23, 2024 11:59pm #31651This is just a question out of curiosity. I feel like certain references appear so often, that I almost start to know them by heart. Not just the model, but the same exact pose, prop, lighting,... On the other hand, it can't be that the overall pool of references is just so small, that I basically know all of them by now, as every now and then an image pops up, that I have never seen before.

I have to add, that I had the same phenomenon, when I was drawing on quickposes.com . Are those just the downsides of working with an imperfect random number generator, or are some images deliberately referenced multiple times in the pool?May 23, 2024 11:24pm #31649Yes Polyvios, but generally the problem in drawing faces is to NOT get them to look like caricatures. Which requires a whole lot of detail, with quite carefully measured proportions. Famous cartoonists and caricaturists often use specific shortcuts, which can indeed be drawn quite quickly. But drawing Elmer Fudd, Eric Cartman or Charlie Brown in under 30 seconds will neither teach me a lot about portrait drawing, nor even about developing my own caricature shortcuts. Even Manga faces are already a bit too complex to gain very much from one minute drawings, although they might be at the border if you really train on repeating them quickly.

I tried quicksketching portraits myself and found no value, but I also found no one online, who promotes quicksketching as a good entry into portrait drawing. The usual beginner tips for portraits to more than 50% start with Loomis, and you can't do Loomis under a minute. And those, that do not center on Loomis tend to be more complex, not more simplified.-

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on May 23, 2024 8:28pm.

Aunt Herbert

edited this post on May 23, 2024 8:28pm.

May 23, 2024 10:06am #31644I personally haven't found a solution either, pretty much out of the same reasons. I just use "all of the same length" mode with 3600 seconds as timer.

I mean, there are sometimes street artists in touristy places, who sell quick portraits, but even they take 5 mins.May 22, 2024 2:59pm #31638Probably no, but probably yes.

What I mean is, if I look at my own 30 second sketches, they vary wildly, basically determined by what my goal for the session is, and what my mood in the moment is. If I want to go for line quality and consistent drawing rhythm, there might be barely two or three lines on the paper at all. If I want to focus on perspectivic drawing, there will be a few first primitives, circles or initial sketches of cuboids visible, but rarely enough to make sense to publish, because most audiences could barely even guess the purpose of my lines. If I want to focus on pose, I might start with the line of action stick figure, as it is proposed in the tutorial. If I want to focus on proportion, there might be a lot of details indicated, but not as a goal in itself, but to use as landmarks.

Or, for F's sake, if I am stressed and tired, drawing in the break between two shifts, I might be happy to just watch the pen moving over the paper for a while, and when I am in a bad mood I'll just desecrate the paper until the timer runs out.

So, the one "better" technique? Probably no. But the clearer you learn to distinguish between all the different aspects and subskills of drawing, the more purpose you can assign to your shortys, and the clearer the purpose, the clearer your lines.

Looking at your shorties, I can see, what you are working at, and there is nothing crying out to me: "Oh! my! God! No!". You are focusing on displaying a pose, well, I can understand each of those poses at a glance. The measurement and proportions look natural and convincing, as much as it can be determined on a single glance at that low level of detail.

You say, you wish for clea-R-er lines, you could probably achieve a bit of clea-N-er lines, for example for your heads, by just grinding a bit of oval drawing to improve your manual dexterity there. Or by drawing fewer lines at a slower pace. But I am not certain if I should recommend that, as that does not seem to fit to the purpose of those sketches. You could do that, but it would probably compromise on the goal of simply communicating the pose. Also, these poses are clearly drawn to prepare an underlying construction, while line quality ultimatively is an aspect of rendering. If you aren't dedicated to draw from first lines with a big fat ink brush, those first lines will probably be erased or overdrawn anyways before you end up on the final polish.

The way those timed classes work for me: I try to imagine a specific goal for the session, I use the shorties to test out and reinforce the concept for the session, and then the 5 minute and 10 minute drawings as proof of concept.

Often the problems of my concept won't become apparent within the shorties themselves. For example: I try to find big curves, looks fine at 30 seconds, 1 minute, then when the 5 minute drawing is up and I start to flesh out the details, it becomes apparent, that I took massive liberties with proportions. I got another attempt at 5 minutes, same stuff happens, but I try to make it look at good as possible none the less. When the 10 minute figure is in, and the timer is running low, it's crunch time. If all went well, and I feel like I still have to add to the figure, I'll stop or restart the timer to get going. If the result instead looks funky in not a good way, I'll then try to pin down, WHAT aspect I don't like. And then try to come up with a concept for the next batch.

In the example the proportions went wild, so my next batch of shorties will focus more on measuring and determining landmarks. Or, possibly, I decide, that in spite of the strange proportions I really like the 10 minute results, and even wished that it would look even cooler with even less details and a more abstract rendering, so my next batch will focus on spending less time scribbling and more time on observing the reference and looking for even bigger lines....

The thing is, I don't believe there are "perfect" shorties, and can't be by design. The purpose of shorties is to emphasize one aspect of your final rendered work, they aren't meant to be published, and they don't necessarily look pretty. I could upload pages full of shorties, and basically everybody would just search for polite words to tell me, that is just a bunch of mad scribbles, depending on what aspect I am working on.

Lines are clear, when they have a clear purpose, but the purpose of shorties is only revealed in the final drawing. Which is only a waypoint to define a clearer purpose for your next set of shorties.

Other artists can only tell you about what they experienced on their path, and that may or may not be informative for you, but it can't take the task of defining the purpose of your lines away from you.

Wow, that sounded so preposterously Zen, I'll better stop writing and go back to drawing, before I embarass myself even more.3 -

-

AutorPublicaciones